On a recent warm and breezy Saturday night a few dozen Russians—mostly in their 20s and 30s—crammed into a small Soviet-era apartment in Vakke, a well-heeled part of Tbilisi, Georgia’s capital and, for now at least, their new home. While thousands of their compatriots were enjoying Georgian food and wine in street cafés and Russian-speaking bars, they huddled around a projector, holding what they described as a “home conference”.

Émigré hangouts can be depressing places. This one exuded intellectual energy. The event was well structured, attendees were well behaved, and there was almost no drinking. Over the course of two hours a dozen speakers talked about their past and present pursuits. Their subjects ranged from the “pathology of propaganda” and cleaning up the streets of Tbilisi to recycling, driverless cars and helping people with psychological trauma. In the interval, they sampled home-made snacks, including vegan, gluten-free cake (5 lari—$1.85—a piece). In both form and content, the conference was a snapshot of a country that the attendees wished to live in, and which was now separate from the place they once called home.

Nobody knows exactly how many people have left Russia since the start of the war. Estimates vary from 150,000 to 300,000. About 50,000 are thought to have settled in Georgia, an influx large and sudden enough to push up local rents. It is not just the numbers that matter, but who the émigrés are. Like those crammed into the Vakke apartment, the diaspora consists largely of young, well-educated, politically conscious, active, articulate and resourceful people—in other words, Russia’s intellectual elite. The exiles have taken with them their habits, their networks, their ability to self-organise and their values. That will have profound effects on both the country they have left behind and the countries they have settled in.

Georgia, a former Russian colony and Soviet republic, has itself been on the receiving end of Russian aggression, most recently in 2008. These days around 20% of its territory is in the hands of Russian-backed separatists. Now the country is proing refuge to activists and journalists. Many are too young to remember Mr Putin’s war against Georgia. But they share the sentiment expressed on graffiti around Tbilisi: “Fuck Putin’s Russia”. Much of their energy and drive is being spent trying to ameliorate the impact of Mr Putin’s war against Ukraine.

Tickets to the Vakke conference cost 20 lari. Along with the cake money, the cash went to Emigration for Action, a charity that proes medication for Ukrainian refugees. Ekaterina Kiltau, one of its founders, was the final speaker. “We have come to Georgia, and we have the privilege to do and say what we want, to call the war a war [the word is banned in Russia] and to help Ukrainians,” she told the audience.

Other volunteer projects such as “Helping to Leave” and “Motskhaleba” (which means “mercy” in Georgian) grew out of chat groups on social media. Now they involve hundreds of volunteers helping thousands of Ukrainian refugees escape from the war. Larisa Melnikova, one of Motskhaleba’s co-founders, is a digital designer and a business consultant who used to work for the Russian branch of Boston Consulting Group, an American multinational. She has now turned her skills to writing an internet bot that helps human volunteers sort through requests for help. “I know that if I don’t do anything, I will be in greater pain,” she says. “I never voted for Putin, but I paid taxes in Russia and I bear responsibility for its actions.”

Back in Russia civic activists such as Ms Kiltau and Ms Melnikova helped monitor elections, volunteered for independent candidates and helped ovd-Info, a human-rights organisation that assists the victims of Russian state repression. Had they stayed in Russia and publicly protested against the war, they would most likely be in prison. That is what happened to Alexei Gorinov, a Moscow city council deputy sentenced to seven years in jail for criticising the war, and who rejected the idea of holding a children’s drawing competition while it was happening. “These people are heroes, but I feel I am more useful here,” says Ms Kiltau.

Working as a volunteer in Georgia, she says, is not just about helping Ukrainians but also about preserving their own sense of honour and sanity. “Pain, shame and responsibility” are three emotions that Ms Kiltau feels constantly. Her pain is acute: Rubtsovsk, the small town in Siberia from which she hails, and which was once surrounded by five gulag camps, became notorious as one of the top destinations for parcels sent home by Russian soldiers looting civilian property in Ukraine.

Echoes of history

Like most Russian exiles in Tbilisi, those who gathered in the Vakke “home conference” fled Russia in the first two weeks of the war. They fled because they were afraid, and because they felt stifled by life under a regime that brooks no dissent. Spontaneous and emotional as their exit seemed to them, it was also part of a Kremlin “special operation”. By spreading rumours of imminent arrest or conscription, and sending thugs to harass activists and journalists, it drove those who publicly opposed the war out of the country.

Some were relocated by the firms they worked for. Others went under their own steam. A survey of recent émigrés showed that about a quarter of those who left settled in Georgia. The same number went to Istanbul, and another 15% ended up in Armenia. (These places do not require visas for Russian citizens.) Nearly half of those who left work in computing and it, according to a survey carried out in March. Another 16% were senior managers; 16% more worked in the arts and culture. Only 1.5% of emigrants ever supported Mr Putin’s United Russia party.

Today’s exiles are not the first Russians to flee abroad in the face of repressive rulers. A hundred years ago, during the Russian revolution, many aristocrats, soldiers in the anti-communist White Army, and members of the intelligentsia fled the Bolsheviks, who plunged Russia into a civil war after they seized power. Like their successors a century later, they made their way to Tiflis and Constantinople (modern-day Tbilisi and Istanbul).

Although today’s Russia is not embroiled in civil war, its invasion of Ukraine has cut through families. Arguments have split brothers from sisters and children from parents. (Such torn ties are the subject of a documentary by Andrei Loshak, a Russian film-maker who is among those to have moved to Georgia). Lately a barely detectable, but nevertheless real, tension is rising between those who left Russia and those who stayed, however similar their attitudes to the war. Behind the veneer of composure and energy among émigrés lies the pain of broken lives, a fractured country and homes left in a hurry.

The effects of the latest wave of emigration on Russia’s future is likely to be far greater than the mere numbers suggest. Andrei Zorin, a cultural historian at Oxford University, points out that the loss of the Westernised elite after the Bolshevik revolution in 1917 was ameliorated partly by the rise of bright children from the Russian peasantry, who were eager for education, and whom the new Communist authorities were eager to help.

They were joined by ethnic minority groups within the Soviet Union—Jews from the shtetls, Armenians, Georgians and people from the Baltic states, where literacy levels were highest. The reconstituted intelligentsia—which was dependent on the Communist Party, but often also critical of it—was essential to the state’s ability to develop technology, science and culture. In the 1980s it formed the social basis of Mikhail Gorbachev’s liberalising reforms.

These days, things are different. Having rejected modernisation in favour of traditionalism, imperial nationalism and war, the state ejected Europeanised Russians as superfluous, alien and dangerous. Today’s kleptocratic system squashes social mobility and holds little promise of progress. The departure of the educated class today could end a modernising trend that began in the 18th century, says Mr Zorin.

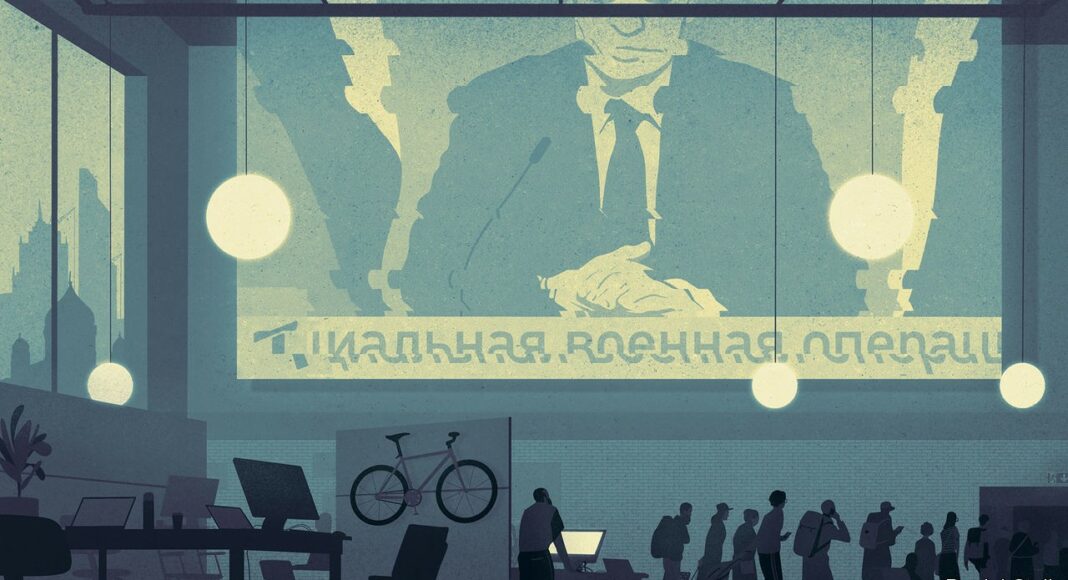

For many years after the fall of communism the modernising elite and the Russian state managed an uneasy cohabitation. In the 1990s and early 2000s the children of the Soviet intelligentsia rejected their parents’ beliefs, mocked anything Soviet and embraced capitalism as they understood it. They did not touch the foundations of the state, but they made Russia more liveable and attractive. They began to transform Moscow into a comfortable European capital, with cycle lanes and trendy art galleries and a quick food-delivery service called Yandex.Lavka—a subsidiary of Yandex, a home-grown tech giant.

Ilya Oskolkov-Tsentsiper is a media manager in his 50s who championed many of Russia’s most successful urbanist projects, including Afisha, one of Moscow’s first entertainment-listing magazines. Sitting in a café in Tel Aviv, his new home, he says the transformation began as an aesthetic endeavour. “We imagined and described Moscow not as a depressing and criminalised city with social problems and inequality, but as a bohemian European capital. The project was so successful that we started to believe [the change] was for real,” he says.

Over the past decade or so those decorations became increasingly backed by substance. Younger, engaged Russians created cultural institutions and launched volunteer projects independent of the state. They helped children with autism, opened shelters for the homeless, recorded podcasts about Russian literature and occasionally came out on protest marches. A survey of exiles conducted in March showed that 90% are interested in politics and 70% have donated money to non-government organisations and opposition-friendly media.

“We believed that our habits and our social practices would make the country humane; that our small deeds would have an effect,” says Sofia Khananishvili, a 23-year-old university graduate who used to teach literature at a school in Moscow. These days she works in a bookshop in Tbilisi called Dissident Books which she and her friends have opened. Among its titles is a volume called “Youth in the City: Cultures, Stages and Solidarities”.

Ms Khananishvili and her contemporaries were never in charge of the state, but they managed to co-exist with it. “We did not touch them and they did not touch us,” says one of her friends, an it specialist. They lived in the folds of the empire, benefiting from Russia’s oil-driven economy but trying to build their own lives apart from a state that was growing increasingly militaristic and repressive.

Few people tell the story of the relationship between the modernising class and the state as well as Ilya Krasilshchik, a media manager, and his girlfriend, Sonia Arshinova. At 35 Mr Krasilshchik had already been the youngest editor-in-chief at Afisha magazine; the publisher of Meduza, an independent online outlet based in Latvia; and more recently an executive at Yandex.Lavka, the food-delivery company. He started getting warnings about the war from inside Yandex back in November. The day after it started he met up with Ms Arshinova in a coffee shop in Moscow. “Everyone was talking about evacuation, looking up flights,” she recalls.

Ms Arshinova, who is 26, was a programme director at Strelka, Moscow’s flagship design and architecture institute. (Its rooftop bar was once a haunt of the beautiful and the well-connected.) When the war against Ukraine began she was working on bringing foreign experts to give lectures to a Russian audience on urban design. They never came. That day, she recalls, “The bubble burst and the shit was dripping down our eyes. We were behind the enemy lines and the enemy was our own city and our own country. We capitulated.”

A few weeks after they moved to Tbilisi, Russian authorities opened a criminal case against Mr Krasilshchik. An Instagram post about Russian atrocities in Bucha, a city in northern Ukraine, was enough to attract charges of “discrediting Russia’s armed forces”. These days Mr Krasilshchik scoots around Tbilisi on his red scooter, recording podcasts and running a new start-up, a half media and half support group called “Helpdesk Media”. It grew out of his Instagram account, which has 150,000 followers, and has the consumer-friendly interface of a Yandex service.

Instead of fast food, it delivers advice to people who need logistical, psychological or legal help. It also tells the stories of people affected by the war: the dead, the wounded, the refugees and the émigrés. “Our focus is men and women at the time of war whose lives have been uprooted and destroyed whoever they are,” he explains.

Most émigrés recognise that they are both lucky and privileged to have been in a position to leave. Many see their situation as temporary, and continue to support themselves by renting out their apartments in Russia. (By May, flows of money from Russia to Georgia had risen tenfold.)

Some of those who fled in the first weeks of the war, and who are not under an immediate threat of being arrested, have even been back to Russia temporarily, to see their parents or take care of personal affairs. “It is the strangest feeling. You go back and everything looks exactly the same—the same dentist, the same shops, the same restaurants—but everything has changed,” says Lika Kremer, a Russian podcast producer. The façade of a well-heeled European city is still there. But it has been hollowed out.

It is the silence and the absence of any overt sign of war that is most unbearable, says Ms Kremer. Unlike Ukraine’s refugees, many of whom choose to return to their homes as soon as they consider it at least somewhat safe, many of Russia’s exiles feel they have no country to go back to, and struggle to define what “Russia” actually means. “We have our identity, and our social connections, but no country of our own,” says Ilya Venyavkin, a historian.

Next year in Moscow

The war, and physical separation from Russia, have inspired the idea of a different Russian nation, one that does not depend on an imperial identity, or even on geography. The first step for those pursuing that idea, argues Andrei Babitsky, a journalist who spends ten hours a week learning to read and write in Georgian, is to rid themselves of imperial arrogance. “I share this arrogance. Even today…I cannot stop thinking of the Russian language and Russian culture. My culture. I would gladly give it away entirely for a real peace, but I still cannot help thinking how my language is going to be alive after so many people have been killed in its name,” he wrote in a recent column.

Some exiles talk about creating a virtual state, where social structures can be built independently of any form of government or even geographical location. “Russia is not about longitude and latitude. The Russian diaspora is intellectually strong, motivated and emotionally charged, so it will undoubtedly survive,” says Fillip Dziadko, an author and publisher. “And we have learned to live without the state.”

Their hope is that the internet, and their own energy, will allow them to retain their presence in the same information space as their peers who stayed behind. For now at least, there are still holes in Russia’s regime of online censorship. YouTube is still available. vpn software, which can mask the websites a user is looking at, gives the tech-savvy access to the outside world. Independent media organisations such as Meduza and tv Rain have decamped to Riga, the capital of Latvia, and shifted their operations online.

Shimon Levin, an Israeli rabbi who was born and bred in Russia, who grew up with Russian literature and spent years serving the Jewish community, sees parallels between such thinking and the experience of the Jews, who managed to keep a distinct culture alive for thousands of years. The reasons Jews succeeded in keeping their identity, he explains, was that they put intellectual freedom and books, not land, at the centre of their national consciousness.

“Geography is an important marker of national identity, but identity is dynamic and can only thrive if it gets enriched by new meanings,” he continues. “If the Russian intellectual elite manages to develop its non-imperial identity and to focus on how to live in a new reality and what the “wonderful Russia of the future” [a term coined by Alexei Navalny, Russia’s opposition leader] should look like, it might at least partially compensate for the loss of their motherland.”

The current wave of emigration has a slogan—Poka Putin Zhiv, or “While Putin is Alive”. Nobody knows how long that will be, though time is certainly on the émigrés’ side. Most are in their 20s and 30s; Mr Putin turns 70 later this year. But despite their optimism, it is not certain that they will ever go back. It is even less certain what Russia will look like when the war ends. “The ongoing exodus of Russia’s educated Westernised class could be Russia’s last wave of emigration,” Mr Zorin says gloomily, “since there are no ways of reproducing that elite.” Mr Dziadko, a former student, prefers not to think too far ahead. “We don’t know where we are going to land,” he says. “Because we are still in flight.” ■