There is a passage in John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath that details an exchange between a representative of a bank and a tenant they are in the process of evicting. It was published 80 years ago, but still feels relevant today.

“We’re sorry. It’s not us. It’s the monster. The bank isn’t like a man,” the banker tells the tenant.

“Yes, but the bank is only made of men,” comes the tenant’s reply, expecting some kind of reprieve.

“No, you’re wrong there – quite wrong there. The bank is something more than men, I tell you. It’s the monster. Men made it, but they can’t control it.”

I thought of those words recently as I sat in a courtroom in Charleston, West Virginia, listening to a drug company executive defend his employer’s role in fuelling the opioid epidemic.

The executive, a former compliance officer for one of the “Big Three” pharmaceutical companies that collectively funnelled hundreds of millions of prescription pain pills to the state, was asked why they had not stopped the shipments when it became clear there was a problem.

“We’re a company. We’re not an enforcement agency and we’re not a regulatory agency,” said Chris Zimmerman, senior vice president of regulatory affairs at AmerisourceBergen.

This notion that a company made up of people cannot be expected to behave like a person, even in matters of life and death, has proven remarkably resilient. It survived from before Steinbeck’s setting of the Great Depression to the boardrooms of corporate America today. Its persistence tells us something about how the opioid epidemic was allowed to grow into the monster it did.

A numbers game

In a landmark lawsuit currently underway in Charleston, the one in which the executive was testifying, authorities in the city of Huntington and Cabell County are seeking some $2bn (£1.5bn) from the three giant healthcare companies, Cardinal Health, McKesson and AmerisourceBergen. They accuse them of creating a “public nuisance” by failing to prevent unspeakably high volumes of prescription pills flooding into the county and city as addiction rates and overdoses soared.

The lawsuit does not attempt to bridge the philosophical die between person and company, it does not argue that these companies needed to behave like a human, only like a responsible company, to have prevented the worst of this crisis.

Our Supporter Programme funds special reports on the issues that matter. Click here to help fund more of our public-interest journalism

The trial has offered a disturbing insight into how decisions made a decade ago in boardrooms far away would go on to impact the lives of so many here in West Virginia.

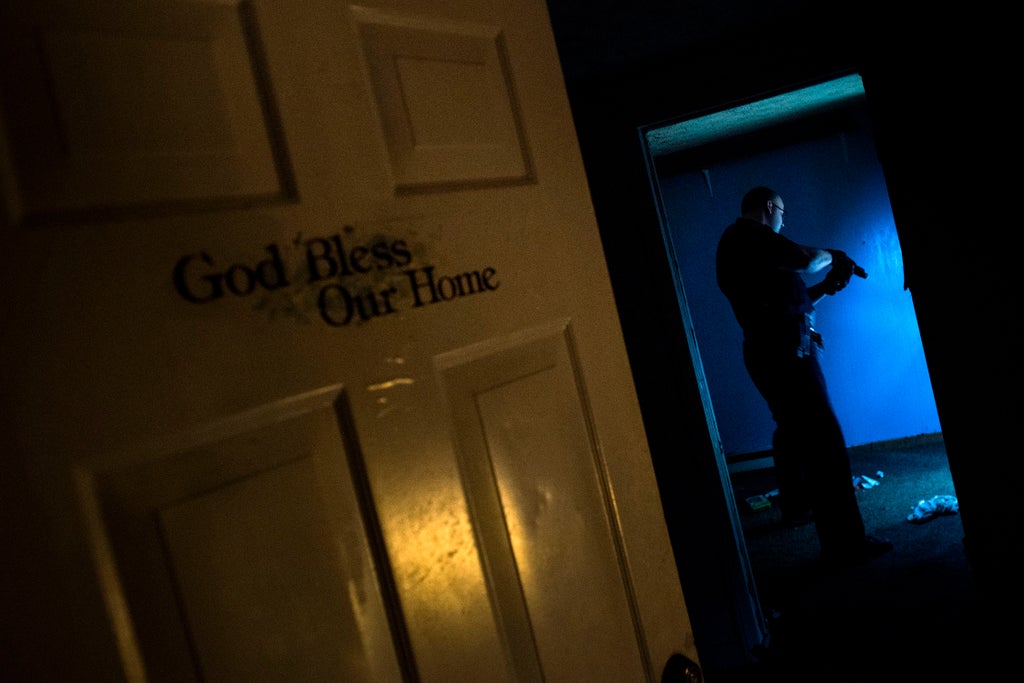

As the trial was underway, I travelled between the courtroom and Cabell County to trace the impact of those decisions. It was a jarring experience. One day I was listening to drug company executives explaining in cold terms why their actions made sense for the company. A few days later I met the people still dealing with the fallout from these decisions.

This lawsuit targets the drug suppliers, rather than the manufacturers. As such, it is a case that centres on numbers – specifically, on an argument that the sheer number of prescription opioid pills being delivered to Cabell County was so high that the suppliers should have stopped supplying them.

In the opening days of the trial, Craig McCann, appearing as an expert witness for plaintiffs on day six of proceedings, was asked to crunch some numbers on a calculator for the court to determine the total number of pills distributed by these three companies. He paused for a moment before answering.

“The calculator won’t take numbers that large,” he said. “I’m sorry.”

My mother was an addict most of my life. My sister passed away from a drug overdose from pills when she was 24. I had a lot of stress on me – I wanted to escape and I knew how to escape

The court heard that some 109.8 million doses of hydrocodone and oxycodone were shipped to Cabell County between 2006 and 2014, and that the Big Three supplied almost 90 per cent of them.

Lawyers for the county implored representatives of the drug companies to give their opinion of the astronomical numbers. Variations of those words – “We’re a company” – would invariably follow.

The executive’s telling phrase was the first of many occasions during the trial that exposed the disconnect between decisions made in a boardroom and the impact they would have on the ground, and the people whose lives they changed.

Living with the ‘pill mills’

“The pharmaceutical companies and the distributors knew what they were doing. They knew what they were dumping into the area and they just did not care,” said 36-year-old Lisa Smith, at a recovery meeting near Huntington.

Smith grew up around drugs and the trouble they brought. Like many others across the state, it all began with prescription pill abuse. They were always around and always available.

“I started out on pills and before I knew it I was hooked. I struggled for years with pills,” she said. “My mother was an addict most of my life. My sister passed away from a drug overdose from pills when she was 24,” she said. “I had a lot of stress on me. I wanted to escape and I knew how to escape.”

Over eight years, the “Big Three” shipped 63.48 doses of hydrocodone and oxycodone per person to Cabell County, more than three times the national average. One pharmacy in Huntington took 35,000 units of oxycodone a month – seven times the national average.

Smith remembers how easy it was. Locals called these high-volume pharmacies and doctors “pill mills”, and they were everywhere.

“You really didn’t have to have any kind of proof that there was something physically wrong with you. The pill mills didn’t even ask you anything. They would just prescribe the medication. And usually, the pharmacy was in the same building as the doctor. It was all in one place,” she said.

According to the Big Three, it was up to the doctors, the pharmacies and the Drug Enforcement Agency to stop abuse. Their job was to report “suspicious” orders but not enforce shutdowns, they said.

Around 2012, new regulations on prescription opioids reduced their availability across West Virginia. But thousands of people were already addicted and simply turned to illicit drugs like heroin instead. Today, the more powerful synthetic drug fentanyl is responsible for most fatal overdoses.

Last year, West Virginia suffered a record number of fatal overdoses caused by opioids. At least 1,099 people died, according to the state’s department of health – some 962 with fentanyl in their system.

The pills dried up and the heroin came around. I went from heroin to fentanyl and meth and crack and everything. I mean, we did everything. There was not a drug that I wouldn’t do

The plaintiffs have tried to draw a direct line between the prescription pill crisis and the illicit opioid crisis Huntington faces today. The $2bn they are asking for is not compensation for historic damage, but to deal with the current crisis.

In the first days of the trial, former West Virginia state public health officer Dr Rahul Gupta gave a broad overview of the different phases of the opioid epidemic. He detailed how the new restrictions on prescriptions gave rise to a rapid rise in heroin use as addicts tried to avoid withdrawals.

Lawyers for the defence argued that they have no control over the illicit drugs that are causing the crisis today, and therefore it is not their responsibility.

Smith sees things differently.

“The pharmaceutical companies dumped pills in this area for years, and then they quit prescribing the pills and filling prescriptions, that’s when the heroin came,” she said, mapping out her own addiction journey along those lines.

“The pills dried up and the heroin came around. I went from heroin to fentanyl and meth and crack and everything. I mean, we did everything. There was not a drug that I wouldn’t do,” she said.

Lives damaged forever

Much of the trial has been focused on numbers and charts. Dense lines of questioning about what a reasonable number of deliveries should be, and questions of responsibility. But there have also been times that the disconnect between the companies and their patients veered into something else.

One of the most shocking moments of the trial also came during Zimmerman’s testimony. A series of emails exchanged between executives at AmerisourceBergen, Zimmerman included, mocked “pillbillies” who travelled to other states to fill opioid prescriptions when regulations were introduced in West Virginia and Kentucky.

The reference to “pillbillies” was contained in the lyrics of a parody song that was supposed to be sung “To the tune of Beverly Hillbillies”.

“Come and listen to a story about a man named Jed

A poor mountaineer, barely kept his habit fed.

Then one day he was lookin at some tube,

And saw that Florida had a lax attitude.

About pills that is, Hillbilly Heroin, ‘OC’,

Well the first thing you know ol’ Jed’s a drivin South,

Kinfolk said Jed don’t put too many in your mouth,

Said sunny Florida is the place you ought to be

So they loaded up the truck and drove speedily

South, that is.

Pain Clinics, cash n’ carry

A Bevy of Pillbillies!”

Mr Zimmerman said he “shouldn’t have sent the email”, when asked about it in the courtroom, but insisted it was taken out of context and that the corporate culture at AmerisourceBergen was of the “highest calibre”, the Mountain State Spotlight reported.

The emails were sent in 2012, at a time when the prescription opioid crisis in West Virginia was near its peak. Just a few years later, West Virginia had the highest overdose rate in the country.

Read more special reports from our Supporter Programme

For the executives, it was a playful joke. For Natasha Robinson, who I met in the days after Zimmerman’s testimony, it was a very real upheaval, a period of desperation.

“I remember when the pill mills shut down here when I was 15,” she said. “All the doctors started getting shut down. People started getting sued and you know, everything else.

“My mom literally packed all of us up and we moved to Florida just so they can go somewhere to get pills.”

Thousands of others did the same. It was one of the many ways that people’s lives were uprooted and damaged forever by decisions made in boardrooms far away.

Even those who have, against all odds, gone through a difficult recovery and are now clean, will never be truly free from addiction. And many of them are still left with broken homes and families as a result.

The Big Three pharmaceutical companies would like to move on from the opioid crisis. It ended for them a decade ago when their products were no longer the biggest problem. But it hasn’t ended for the people of Huntington, or for the people whose lives have never been the same since they picked up one of their pills all those years ago.