Among the Cold War-era military regimes in South America — including many backed by the United States — the 35-year reign of Gen. Alfredo Stroessner in Paraguay stood out for its police-state surveillance and authoritarian brutality.

Martín Almada, who died March 30 at 87, was one of its most prominent victims, a former schoolmaster, lawyer and rights activist who endured three years of imprisonment and torture, and the sudden death of his wife — officially reported a suicide — who had been forced to listen to his agonizing screams.

He was freed in 1977 and went into exile in France a “broken man” but was eventually recognized as one of Paraguay’s most notable heroes. After Stroessner was forced from power in 1989 in a military coup, Dr. Almada returned to the capital city of Asunción and uncovered a state archive of paperwork and recordings detailing decades of torture and killing. The trove, proving acts long denied by state authorities, opened the way for a widespread legal reckoning.

The cache, which became known as the “archive of terror,” offered a gruesome timeline of atrocities as the Stroessner regime jailed or killed tens of thousands of perceived political opponents, leftist scholars, students and others.

The documents were used in trials in Paraguay of Stroessner-era police and military officials, including the conviction in February of a once-feared torturer, Eusebio Torres, who carried the nickname “the Whip” for his beatings. During proceedings of Paraguay’s truth commission probing Stroessner regime crimes, Dr. Almada brought legal claims on behalf of his late wife.

For the wider region, the files proed a deeper accounting of the repression and bloodshed carried out under a clandestine pact called Operation Condor, which linked Paraguay and five other South American military-supported juntas in efforts to crush left-wing dissent beginning in the mid-1970s. The network included U.S.-backed dictators such as Chile’s Gen. Augusto Pinochet and the Argentine junta responsible for the country’s “Dirty War” that claimed as many as 30,000 lives, rights groups estimate.

“I felt that each folder we opened up would help us go back to the past and understand the regime of terror which we suffered,” Dr. Almada told the BBC in 2002. “Every document revealed terror and tragedy.”

In the archive, Dr. Almada and a judge, José Agustín Fernández, found a critical historical record: an invitation to the head of the Paraguayan secret police for the meeting that launched Operation Condor in Santiago, Chile, in November 1975. The other documents uncovered became part of efforts to prosecute Pinochet before his death in 2006. The records were cited in other human rights cases in Chile and elsewhere.

Julieta Heduvan, a Paraguayan foreign policy specialist who contributes to journals including Americas Quarterly, described the significance of the documents as “immeasurable” for historians. “Also because they deprived political and judicial powers of excuses to evade state-led investigations into human rights violations in Paraguay,” she said, “as well as hindering the process of proing reparations for the victims.”

‘Intellectual terrorism’

Martín Almada was born on Jan. 30, 1937, in Puerto Sastre in northeastern Paraguay and as a boy moved with his family to San Lorenzo, a city near Asunción. His parents found work in factories and small shops, and Martín sold pastries on the street to help bring in extra money.

He graduated from the National Academy of Agronomy with a degree in education in 1963 and worked as a classroom teacher and principal. In 1968, he received a law degree from the National University of Asunción and took on pro bono legal work including advising impoverished villagers and farmers on housing and land rights issues.

As an educator and lawyer, he headed collectives that carved paths outside state controls, including building housing for teachers and promoting unions. In a bold slap at the military, Dr. Almada once proposed that teacher salaries be raised to match soldiers’ pay.

At another point in the late 1960s, he came across a banned book by the Brazilian philosopher Paulo Freire, who saw literacy and education as powerful tools for political change. “We said that school is the gateway to democracy,” Dr. Almada said. For the Stroessner regime, such calls to expand learning among the rural poor and others were viewed as threats to the state’s monopoly on thought.

Dr. Almada and his then-wife, Celestina Pérez, were placed under full-time watch by the secret police. “That was my first sin, my first crime,” he told the PBS show “Frontline” in 2007, “having read a book by Paulo Freire.”

At the National University of La Plata in neighboring Argentina, Dr. Almada received a doctorate in education in 1974 and wrote a dissertation arguing that Paraguay’s education system supported the elite’s dominance and reinforced economic inequities. “When I returned,” he said on “Frontline,” “the Argentinean police had sent my dissertation to the Paraguayan police.”

On Nov. 25, 1974, Dr. Almada was arrested for “intellectual terrorism,” a charge designed to send a chilling message to his wife and others who joined them in dissent.

Dr. Almada said he expected to die at the hands of state torturers. Day after day, he endured beatings and electric shocks. He said he was once dunked into a tub of human excrement. His wife, who was under house arrest, was forced to listen to his howls of suffering. “The telephone,” he said, “was used as an instrument of psychological torture.”

She was shown clothes that police claimed where soaked in Dr. Almada’s blood. Dr. Almada said his jailers a demanded information on anti-Stroessner exile groups in Chile and Argentina. He refused. After nine days, they told Dr. Almada’s wife a fabricated story that he died from the punishment — apparently hoping that she would reveal details of their activities that he would not. The next day, she was found dead.

Authorities claimed it was suicide. Dr. Almada always insisted she had a heart attack. No doctor would attend to her, he said, in fear of police scrutiny for coming to the aid of a woman under suspicion. “She died of grief,” he said, always calling her a “martyr” of Stroessner’s regime.

He was freed in 1977 after pressure for his release from Amnesty International and faith groups, including the Committee of Churches of Paraguay. He was 40 years old but stooped, weakened from his ordeal and with serious wounds to his eyes that later required operations to help heal. As part of the release deal, he signed a document that amounted to a confession of treason. The wording, said Dr. Almada, gave the regime the validation it wanted.

“I have to say it’s true,” he said in the PBS interview. “If I do not sign, they kill me.” He was granted asylum in Panama, and then moved to Paris, where he began work with the United Nations cultural agency UNESCO in 1986.

After Stroessner was overthrown and allowed passage to Brazil, Dr. Almada returned to a Paraguay ravaged by nearly two generations of violent crackdowns. An entire “thinking class” of artists, journalists and other intellectuals were maimed or dead, he said. Political forces with connections to the regime, the right-wing Colorado Party, still held control. Few dared to raise questions of accountability for the past. Historical amnesia became de facto policy.

“I returned to Asunción, went to the courts and asked to be given the right of access to my files,” he recounted. “And the police replied, ‘There were no files’ because [no records showed] I had never been in prison.”

Then in late 1992, he received a visit from the disgruntled wife of a former regime bodyguard. “Her husband drank a lot and went with other women,” he told the Miami Herald. “She really hated him.” She gave Dr. Almada a tip: The head of Stroessner’s secret police was obsessive about keeping paperwork on everything from arrest logs to torture schedules. The records, she said, were stashed at a police station in Lambaré, a town near Asunción.

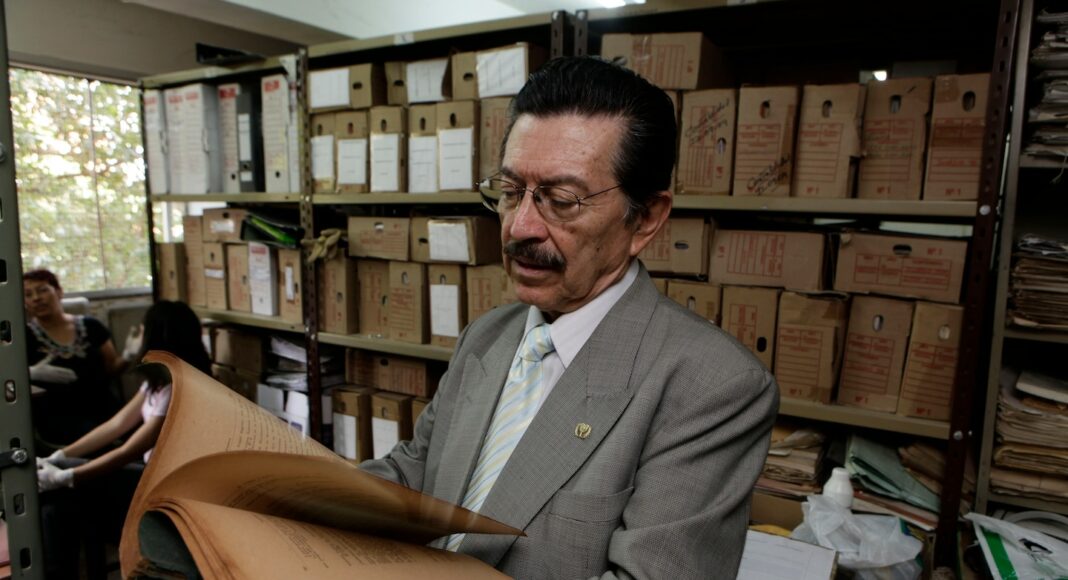

When Dr. Almada entered the storeroom in late December 1992, he was stunned to see towers of boxes holding more than 700,000 pages. “It was full, much more than we thought,” he told the Herald. “It’s the taking of the Bastille. I cried with joy.”

Stroessner died in 2006, at age 93, with the Brazilian government declining to act on Paraguayan courts’ requests for his extradition on homicide charges. Paraguay’s Colorado Party continues to dominate the country, most recently winning elections in May 2023. But the party over the decades tried to blur its connections to the Stroessner regime and reinvented itself as a conservative political machine that had been accused of vote-buying and other tactics to remain in power.

Dr. Almada, however, always kept the spotlight on the Stroessner era — calling it a cautionary tale in a time when autocratic political forces continue to find footholds around the world. In 1990, he established a human rights watchdog group named for his late wife, the Celestina Pérez de Almada Foundation.

“The fragility of our democracies causes in many Paraguayans a nostalgia of the so called “times of order, peace, progress and security,” he said in 2002 after accepting the Right Livelihood Award, sometimes called the “alternative” Nobel Peace Prize. “There were the same times in which Operation Condor eliminated millions of people in front of the passive and accomplice silence of the neighbors.”

Dr. Almada’s death, in a hospital in Asunción of undisclosed causes, was announced in statements that included a tribute from the current president of Paraguay, Santiago Peña.

Dr. Almada and his second wife, María Stella Cáceres, led the human rights group he founded and worked on projects including the opening of a museum to chronicle the abuses under Stroessner’s regime and Operation Condor. His published work includes an account of his years in prison, “Paraguay: la Cárcel Olada, el País Exiliado” (Paraguay: The Forgotten Prison, the Country in Exile).

He had three children from his first marriage. Complete information on survivors was not immediately available.

Dr. Almada recounted to the BBC how he told his jailers that one day he would have the upper hand.

“When I was handcuffed and shackled, I used to say to them that the world was a slowly turning wheel and that sooner or later democracy would come and I would play a very important role,” he said. “I made that up, of course, and I doubt they believed me, but in a way it has.”