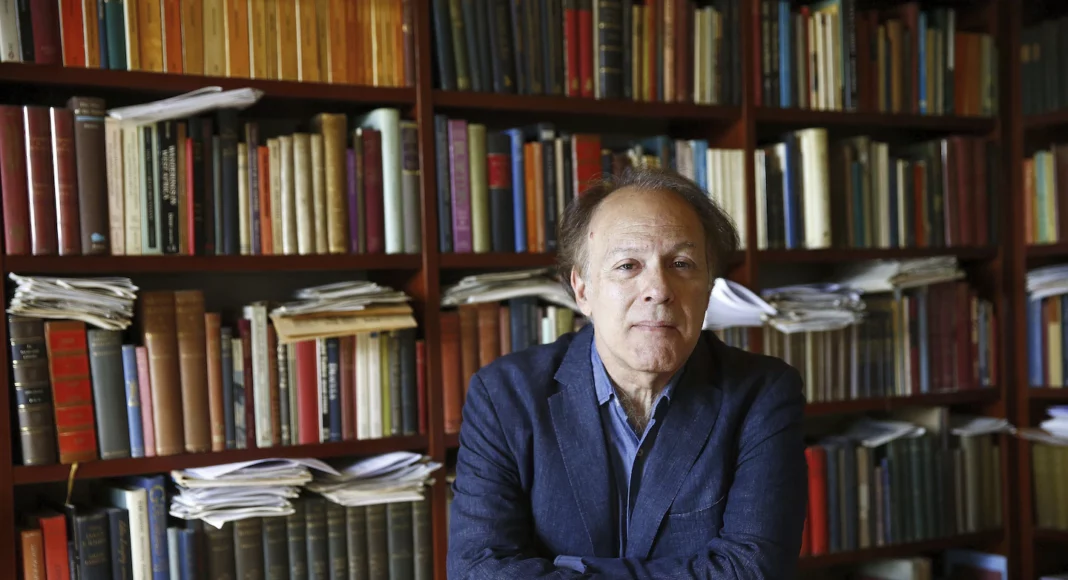

Javier Marías, a renowned Spanish author who used multilayered plots and complex literary structures to explore the labyrinths of spy craft, smoldering obsessions and the tipping points between commitment and betrayal, died Sept. 11 at his home in Madrid. He was 70.

His death was announced by his Madrid-based publisher, Alfaguara, citing pneumonia as the cause.

Mr. Marías’s body of work — more than 15 novels and collections of short stories and essays — was hugely popular in the Spanish-speaking world and translated into dozens of languages including English. He sold nearly 9 million copies, led by his three-book spy saga “Your Face Tomorrow” often regarded as his masterwork.

He remained, however, lesser known in the United States despite having American connections from his father’s university posts and receiving reviews that often placed him among celebrated contemporary authors such as Orhan Pamuk, J.M. Coetzee and Paul Auster.

The overriding themes of Mr. Marías’s novels ranged widely: murder mysteries, international espionage, family secrets and more. He could keep it light or go graphically violent. Yet all his novels had a heavy overlay of emotional and moral fog that left the characters — sometimes interpreters and translators like he was once in real life — trying to grope their way ahead.

“He wrote thrillers like a poet,” said a tribute to the author in the Guardian.

Mr. Marías often spoke of memory as having its own intrinsic weight. The past is always pressing on the present, he told interviewers. It can be as personal as a remembered conversation. Or as collective as the repression of the dictatorship led by Gen. Francisco Franco in Spain from 1939 to 1975.

He built his prose like a scaffolding to hold up the heaviness of the memories, decisions and quandaries of his characters. He could craft sentences that ran for hundreds of words. Adjectives and adverbs sprout everywhere. He could veer off into rabbit-hole digressions that could wend for dozens of pages.

In “Your Face Tomorrow,” a three-volume, 1,274-page spy tale first released in Spanish as “Tu Rostro Mañana” between 2002 and 2007, Mr. Marías takes 150 pages to fully unfold a scene in which someone is nearly killed by a sword.

“A description is also a digression and so is dialogue,” he said in 2017. “You could do without any of those things. To write is precisely that, to delve and to digress.”

That style mostly always worked, giving Mr. Marías a reputation as a virtuoso storyteller whose canvas was much larger than the story itself in the mold of Marcel Proust or Herman Melville.

“As in the best novels and most successful magicians’ acts, one comes away heavy with emotion, wondering how in the world he pulled it off,” said a 1997 review in the Sydney Morning Herald of the English translation of “Un Corazón Tan Blanco,” or “A Heart So White,” an elliptical plot in which an interpreter comes to realize he barely understands his family or himself.

This kind of onion-peel plot was Mr. Marías’s favorite ground. His main characters often confronted moral ambiguities and crossroads. In the epic “Your Face Tomorrow” — a reference to Shakespeare’s “Henry IV” when elder son Hal begins to realize that he is turning against his former companions — a Spanish translator is recruited by British intelligence but later questions his role as interpreter and everything the spy cell stands for.

His imagined worlds straddled between the moral grayness of John le Carré’s spy novels and the allegorical sweep of Miguel de Cervantes’s “Don Quixote.” Fiction, he said, can be more reliable than reality to getting nearer to truths.

John le Carré, who lift spy novels to literature, dies at 89

“The only things that can be fully told, without rectification, without the possibility of someone saying, ‘No, no, no, no, no. That’s not the way it was,’ is fiction,” Mr. Marías told the Danish arts website Louisiana Channel in 2018.

In his own life, Mr. Marías also presented many sides.

He professed government-skeptic libertarian views, but praised how the European Union helped Spain became “a normal European country” after the dictatorship. He sometimes supported the national accord, the “pacto de olo,” or pact of forgetting, after Franco’s death that blocked blame-casting over his regime for decades; other times, he questioned whether the pact left the country in a psychological straitjacket.

In Madrid, he rented two nearly identical apartments near Plaza Mayor. One had dark furniture, the other had the same decor in white. A Paris Review journalist wrote that both were cluttered with stacks of books, DVDs of American movies (many starring comedian Jerry Lewis), and TV series including “Bonanza” and “Friends.”

He liked to playfully note that his own literary journey began in Paris’s decidedly non-chic side during the summer of 1967 helping his filmmaker uncle, Jesús Franco, who churned out mostly low-budget flicks such as “In the Castle of Bloody Lust” and “Marquis de Sade: Justine” starring Jack Palance and Klaus Kinski. The B-movie settings became the backdrop for Mr. Marías’s first novel, “Los Dominios del Lobo” (“The Domains of the Wolf”) in 1971.

Mr. Marías took some fun in being “king” of the imaginary monarchy of Redonda, a real uninhabited Caribbean island in Antigua and Barbuda that was once self-declared a “kingdom” by an eccentric shipping magnate in the late 19th century.

Redonda has become a sort of whimsical realm for authors, artists and others who create what is widely called an “intellectual aristocracy.” Mr. Marías became “Xavier I” in 1997 after the abdication of British author Jon Wynne-Tyson, who had once visited the island. Mr. Marías never got around to it.

“I have never been monarchic,” he joked in a tongue-in-cheek interview with the Paris Review.

‘Dialogue’ as translator

Javier Marías Franco was born Sept. 20, 1951, in Madrid, the son of writer Dolores Franco and Julián Marías, a philosopher who opposed Franco’s Nationalist side in Spain’s 1936-1939 civil war and faced possible execution after Franco’s forces took control. (The family name of Mr. Marías’s mother is no relation to the dictator.)

Mr. Marías’s father was banned from teaching and took two visiting professorships in the United States, the first at Wellesley College in Massachusetts and then at Yale University in Connecticut. That experience gave the young Mr. Marías a foundation in English that he would refine as a translator after his graduation in 1973 with a degree in philosophy and literature from Complutense University of Madrid.

From 1983 to 1985, Mr. Marías lectured at the University of Oxford on the theory of translation — and used his time there as fodder for “All Souls” (1989) about a fictional relationship between a student and a visiting Spanish professor.

Many literary observers, such as University College London professor Gareth J. Wood, drew links between Mr. Marías’s expressive style and his ability to render in Spanish the nuances and complexities “in dialogue” with writers such as Laurence Sterne, Thomas Browne, Vladimir Nabokov and William Faulkner.

Mr. Marías said that his ideal literature school “would require students to know at least two languages and translate books.”

Survivors include his wife of four years, Carme López Mercader, an editor; two stepchildren; and three brothers. Complete information on survivors was not immediately available.

Among his prizes was the International Dublin Literary Award in 1997 for “A Heart So White” and Spain’s highest literary award for the crime tale “The Infatuations” (2011). He turned down the Spanish prize, saying he did not want to be seen as “favored” by the government.

In the book, he may have taken a self-deprecating jab at the Nobel Committee for never having received the prize. A secondary character, a pompous author, has already written his Nobel acceptance speech — in Swedish.