Ειδήσεις Ελλάδα

Comment on this storyComment

You’re reading an excerpt from the Today’s WorldView newsletter. Sign up to get the rest free, including news from around the globe and interesting ideas and opinions to know, sent to your inbox every weekday.

Nuclear security risks are rising for the first time in a decade, according to an annual index released Tuesday by the Nuclear Threat Initiative, a Washington-based watchdog nonprofit that looks beyond the well-known nuclear threats such as weapons proliferation, and toward less widely considered problems, such as the storage of weapons-usable uranium that could be exploited by terrorist groups or the safety of nuclear sites during conflicts.

The report marks the first time that the organization’s Nuclear Security Index, in an attempt to piece together a big picture of the global nuclear threat, finds that security had gotten worse since the dataset’s origin in 2012. The report also comes amid spiraling geopolitical tension over conflict near nuclear sites in Ukraine and stalling efforts at nonproliferation and international regulation.

“This diminishing commitment to reducing nuclear risks is deeply disturbing,” Ernest J. Moniz, chief executive of the Nuclear Threat Initiative and the former U.S. secretary of energy in the Obama administration, writes in an introduction to the index. The world is “unraveling hard-fought progress on nuclear security dating back to the end of the Cold War,” he says.

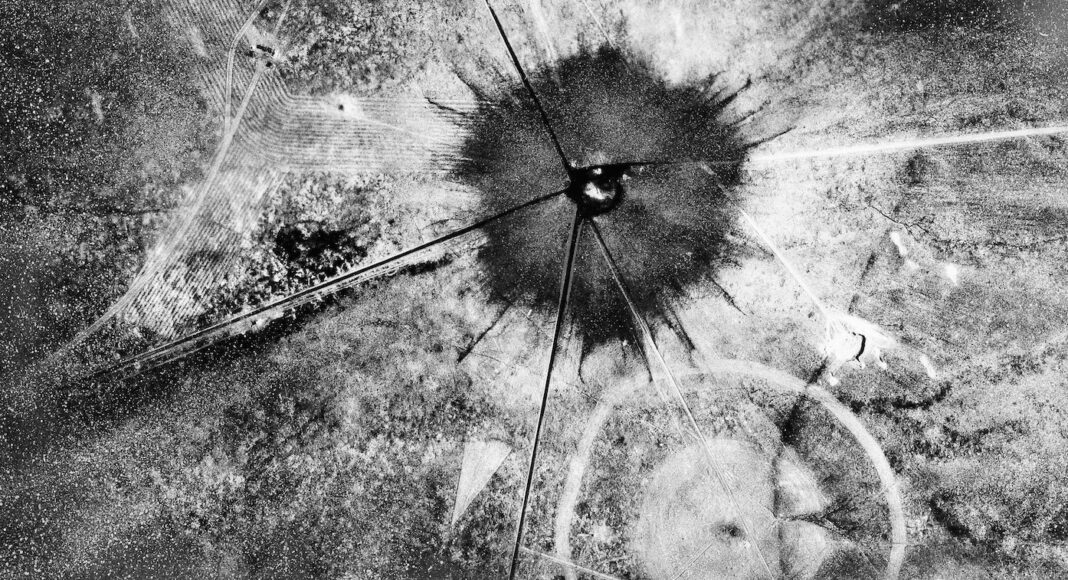

The report coincides with a renewed moment of interest in nuclear Armageddon, prompted by talk of the weapons in the context of the war in Ukraine, and in popular culture, including this week’s release of the film “Oppenheimer” — a historical drama depicting U.S. scientist J. Robert Oppenheimer’s quest to become “father of the atomic bomb,” and to shape its impact on the world.

Recent events in Ukraine have also added to the drama. President Volodymyr Zelensky has repeatedly warned that Russian forces are planning a “terrorist act” at Europe’s largest atomic power station, Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant, which has been occupied since early in Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine last year.

Why the world is worried about Russia’s ‘tactical’ nuclear weapons

The renewed concern is understandable: Some Kremlin officials have openly suggested that Russia could use some form of nuclear weapon if pushed too far in the conflict, while Russian troops left the infamous site of a Soviet-era nuclear disaster, Chernobyl, in a dangerous state of ill repair after a months-long period of occupation and looting last year.

Such risks are only the surface indications of the deteriorating situation, however. The Nuclear Threat Index reported that stockpiles of separated plutonium are growing rapidly in the civilian sphere.

Separated plutonium, along with highly enriched uranium, is a type of nuclear material that can be used to make a weapon. The index found that finds that “since 2019, global inventories of separated civil plutonium have increased by 17,000 kilograms [almost 19 tons], enough material for more than 2,100 nuclear weapons,” mostly due to reprocessing for commercial nuclear plants.

Britain, France, India, Japan and Russia all have high levels of separated plutonium due to its use in nuclear power plants, while the United States also has a high supply due to dismantled nuclear weapons, the index found.

In the 75 years since Hiroshima, nuclear testing killed untold thousands

The report also pointed to severe failings in the protection of weapons-usable nuclear material, with “little progress” made since 2020 toward improving security and threat prevention in counties that had it. More than a third of countries and areas with nuclear facilities were found to have no regulatory measures in place for protecting those facilities during “a natural or human-caused disaster” — despite the recent experiences in Ukraine.

Iran and North Korea, two countries at the center of geopolitical standoffs over their nuclear programs, were ranked last in the index for their ability to protect nuclear sites from theft or sabotage. The report found that risk environments had worsened in 12 of the 22 countries with weapons-usable nuclear materials, largely due to worsening political instability and rising illicit activity by nonstate actors.

There are some areas where security efforts are improving. The index finds that many countries in the global south have improved in their rankings, perhaps showing that nuclear security is less about wealth and more about effort and attention.

Recent years have seen a sustained movement away from the use of highly enriched uranium, one of the materials that could be used to create a nuclear weapon (most countries have switched to using low-enriched uranium, though in 2021 Iran became the first country in almost two decades to produce it — another worrying data point).

The report points to the importance of the International Atomic Energy Agency, a 65-year-old U.N.-linked watchdog organization that appears to be becoming only more relevant. Under the proactive leadership of Argentine diplomat Rafael Grossi, the IAEA has played a high-profile role in Ukraine, where it has tried to ensure nuclear safety, while it continues to play big roles in North Korea, Iran and in the continuing aftermath of Japan’s 2011 Fukushima disaster.

But the index notes that support for the agency’s role in nuclear security was “inconsistent, even as demands for the IAEA’s attention and resources grow and global risks evolve.” Grossi has come under pressure from all sides in Ukraine, with Zelensky apparently rejecting his calls to make the Zaporizhzhia power plant a demilitarized zone, according to leaked U.S. documents.

A remarkable aspect of the story of the atomic bomb is that its earliest originators were deeply devoted to consideration of its existential implications for humankind in the decades and centuries to come. Oppenheimer himself was an early voice in the debate over nuclear policy, and an advocate for inspections, limits, openness and other approaches that did not gain traction until after the Cold War arms race had barreled out of control. His convictions cost him dearly in an era of McCarthyite suspicions.

In a 1953 essay for Foreign Affairs, Oppenheimer augured that a time would soon come for the “serious discussion of the regulation of armaments,” by which time “there will have been by then a vast accumulation of materials for atomic weapons, and a troublesome margin of uncertainty with regards to its accounting — very troublesome indeed if we still live with the vestiges of the suspicion, hostility and secretiveness of the world of today.”

As the index shows, the world’s governments have a long path ahead toward securing one of humanity’s most calamity-empowering creations.