Ειδήσεις Ελλάδα

Comment on this story

Comment

RIO DE JANEIRO — Down in the polls heading into the Brazilian election last year and under multiple investigations for alleged wrongdoing in office, President Jair Bolsonaro spoke candidly about one of his greatest fears: prison.

“Freedom is more important than life,” he said five months before the October vote. “These days I spend most of my time fighting legal problems. They’re even saying I’ll go to prison. For God in heaven, I will never go to prison.”

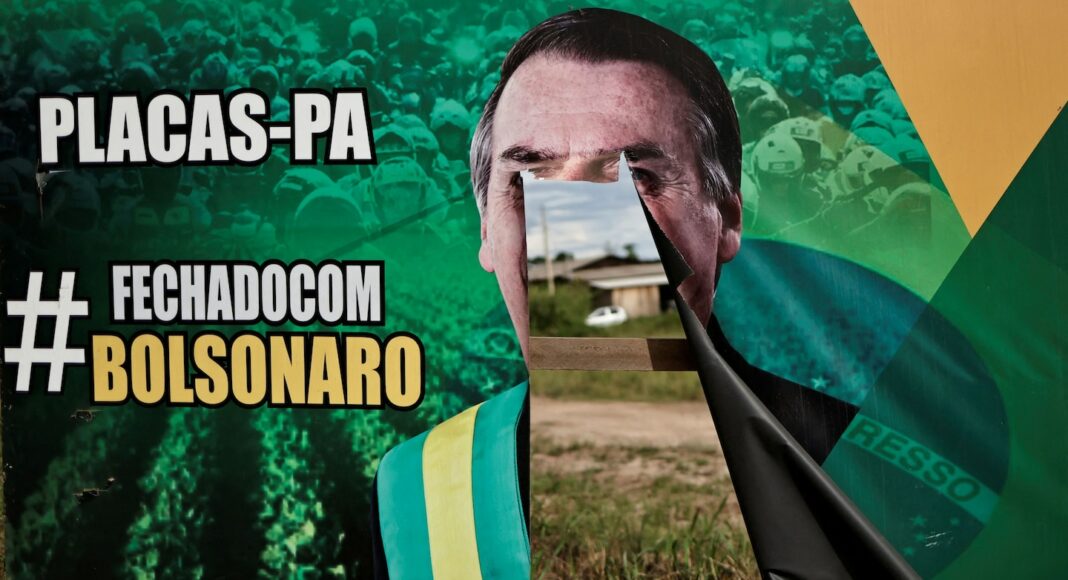

For the race-baiting, LGBTQ-attacking, coronavirus-dismissing icon of the far right, the Jan. 8 riot by his supporters in Brasília after his narrow election defeat has brought those fears closer. In comparison to the U.S. authorities investigating President Donald Trump’s role in the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, officials in Brazil moved quickly to open another criminal probe of Bolsonaro.

But for Bolsonaro, senior judicial officials and legal analysts say, a risk far greater than prison time is the loss of something he appears to value almost as much as his liberty: his political career.

The jeopardy Bolsonaro faces in the criminal investigations against him is far outweighed by the likelihood of sanctions for alleged electoral violations. Those offenses rarely draw prison sentences, but they often result in fines and — more to the point — bans on running for public office for as long as eight years. Such a penalty would prevent Bolsonaro, 67, from seeking a return to public office until the 2030s.

Bolsonaro’s lawyer for the electoral cases said his client sees the allegations against him as “political persecution.” But he conceded that their sheer number amounted to a substantial legal obstacle.

“It’s like if I have to play a game 16 times and I can’t lose a single time,” Tarcísio Vieira de Carvalho told The Washington Post. “It’s very difficult to avoid ineligibility [to run again]. But giving up is neither mine nor Bolsonaro’s profile.”

If convicted of electoral violations, Bolsonaro’s future could begin to mirror that of his political lodestar: Trump. While Bolsonaro was defeated in October, his political allies made gains in Brazil’s Congress and state governorships. The right-wing movement he nurtured in Brazil, built on disinformation, conspiracy theories and anti-democratic rhetoric, might now be strong enough to thrive without him.

“While cries of outrage will persist from some of his hardcore followers, Bolsonaro’s constituency will not necessarily pine for his return,” said Robert Muggah, co-founder of the Rio de Janeiro-based Igarapé Institute. “That leaves room for slightly more civilized right-wingers … to fill the vacuum he has left after fleeing to the U.S.”

One thing is certain: Bolsonaro’s legal problems are legion.

The 16 electoral cases against him are being investigated under Brazil’s electoral court. Six criminal cases are being investigated by the Supreme Court. The electoral court is led by the crusading Supreme Court justice Alexandre de Moraes, who has sought for years to check Bolsonaro’s anti-democratic impulses.

The Supreme Court is handling the criminal investigations in part because Brazil’s pro-Bolsonaro attorney general has been reluctant to open cases against him. Now that Bolsonaro is a private citizen, any criminal charges against him would normally proceed through lower courts.

But legal analysts say any criminal charges are likely to remain in Moraes’s hands, partly because they involve other senior politicians who may be investigated only by the high court.

A key reason Brazil has moved quickly to investigate Bolsonaro is Moraes, who enjoys wide-ranging investigative powers. On Jan. 13, five days after the insurrection, he agreed to a request by prosecutors to add Bolsonaro to a probe into its masterminds and instigators.

Bolsonaro spent his four-year term sowing doubt in Brazil’s electoral system. He called Lula a “thief” and suggested his opponents might try to steal the election. But he has condemned the violence on Jan. 8 and denied any role in it.

Prosecutors, in their request to investigate Bolsonaro, cited a he posted on Facebook on Jan. 10 that questioned his election loss. Although it was posted two days after the riot, and deleted a day later, prosecutors argued it would “have the power to incite new acts of civil insurgency.”

Another piece of eence: A document seized in the home of Anderson Torres, Bolsonaro’s former justice minister and the chief of security in Brasília at the time of the Jan. 8 insurrection. The document appeared to call for the declaration of a “state of defense” that could have been used to try to keep Bolsonaro in power.

“I think the risk of jail time is greater now that it was” before Jan. 8, said Hélio Silveira, a former senior official with the Brazilian Bar Association.

The other criminal cases against Bolsonaro involve allegations of interfering with federal police, spreading disinformation about the reliability of Brazil’s election system and leaking classified information. They also include his statements about the pandemic. As Brazil suffered one of the world’s largest and deadliest outbreaks, Bolsonaro dismissed co-19 as a “little flu” and spread skepticism about vaccines.

Figures close to the court say the criminal investigations require more and stronger eence. There is growing concern in judicial and political circles that arresting Bolsonaro now would turn him into a martyr and risk further unrest by his backers.

“Bolsonaro’s arrest will not happen for now,” said one senior judicial official, who, like others, spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss the sensitive matter. “It will take time. I don’t see the court’s will to do this. Not now.”

But analysts see three of the electoral violation cases as serious. They focus on a meeting with foreign diplomats in July 2022 in which Bolsonaro sought to cast doubt on the reliability of the country’s voting machines, the alleged use of government social programs to boost his campaign, and his alleged misinformation operations.

Several people familiar with the electoral court’s thinking said the judges are likely to try to wind the most robust cases up by May. That’s when Bolsonaro appointee Kássio Nunes Marques gains a seat on the seven-member tribunal.

In the meantime, Bolsonaro’s legal woes have become a political headache overseas.

Rather than stick around to hand off the presidential sash to Lula, Bolsonaro skipped town Dec. 3o for Florida. The visa on which he entered the United States is not publicly known. It might have been an A-1 visa, which is used for diplomats and heads of state. State Department spokesman Ned Price told reporters Jan. 9 that A-1 visa holders have 30 days at the conclusion of their term to leave or apply for a different visa.

For Bolsonaro, 30 days means Monday. But he might hold tourist or business visas that would allow him to extend his stay for months.

A senior State Department official, asked last week about Bolsonaro’s visa status, said he could not comment directly on an indiual’s visa status. But “as a general matter,” he said, “it could well be the case that indiuals come here under an A visa but could [already] have another [visa], whether as a tourist or something else.”

Bolsonaro in an interview with CNN Brasil, suggested he would return to Brazil this month. But one person familiar with his thinking said the ex-president remains concerned about his possible arrest in Brazil.

Democratic lawmakers are pressing the Biden administration to cancel Bolsonaro’s visa should he choose to remain in the United States.

“The United States must not proe shelter for him, or any authoritarian who has inspired such violence against democratic institutions,” 41 House Democrats wrote in a Jan. 12 letter to President Biden.

Should Bolsonaro seek shelter elsewhere, analysts have pointed to Italy, which grants citizenship to ancestors of Italian emigrants. His great-grandfather was born in northeastern Italy, making him and his children potentially eligible.

Media here have reported that two of his sons — the congressman Eduardo Bolsonaro and senator Flávio Bolsonaro — visited the Italian Embassy in Brasília in November to follow up on a citizenship request. Italian officials say Bolsonaro himself has not applied.

The new, right-wing government of Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni could find Bolsonaro’s presence an unwanted distraction.

“I think it’s within Meloni’s best interest to keep herself miles away [from Bolsonaro], as she is desperately trying to acquire a European, democratic and pro-American profile,” said Giuseppe Pisicchio, a former Italian lawmaker who teaches law at Rome’s Unint University.

Dias reported from Brasília. Karen DeYoung in Washington, Stefano Pitrelli in Rome and Diana Durán in Bogotá, Colombia, contributed to this report.